As I’ve already mentioned, I am in the process of (re)reading and analysing the entire Radch series, so here I am, Ancillary Justice keeping my mind busy yet another time.

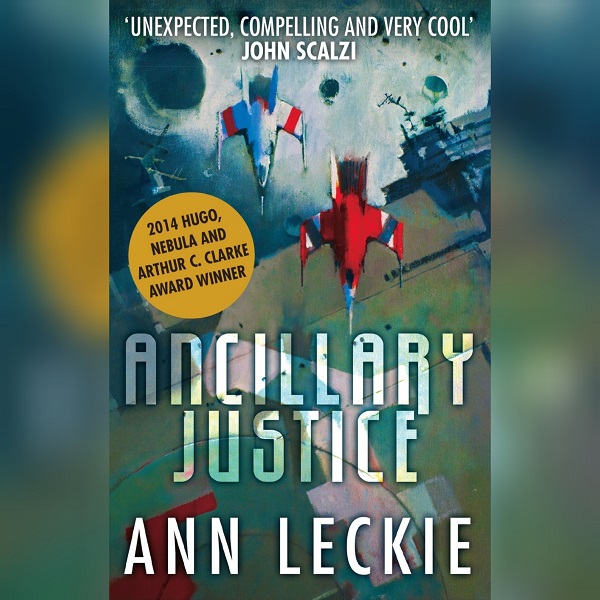

Title: Ancillary Justice

Author: Ann Leckie

Publication: 2013

Genre: Science Fiction

Pages: 409

Standalone or Series: Imperial Radch #1

Content Warning:

Synopsys

Breq, the last surviving “segment” of the artificial intelligence that once animated an entire spaceship and its troops, is on a quest for revenge against the ruler of her world. In her planet-hopping journey, she stumbles upon Seivarden, a former officer from a prestigious family, now stranded and lost after a thousand years in hibernation; despite her mixed feelings towards her, Breq takes it upon herself to rescue Seivarden, a decision that both hinders and helps her other plans.

As she moves forward in her self-assigned mission, Breq also ponders over the facts that had brought her there, gradually revealing past events, as well as the deep roots of her motivations.

Analysis

Style – Written in first person from the point of view of the main character, Ancillary Justice is perhaps most famous for its pervasive use of feminine pronouns, indiscriminately applied to all characters regardless of their physical features and personal identities. The protagonist is, in fact, a sentient AI created by a culture that assigns no importance to sex differences, and whose native language is entirely gender neutral; as such, Breq finds the entire concept and semantics of gender hard to grasp, and despite the occasional effort to adjust to local customs, she tends to address everyone in the same way.

While in universe Breq might as well have flipped a coin to pick her favourite set of pronouns, it’s impossible to ignore some form of authorial intent behind such a choice: in our culture, in fact, masculinity is generally perceived as the default state, and femininity as the (quirky, quaint, diminutive) exception that needs to be pointed out. If Breq had casually misgendered everyone as male, the discrepancy could have easily slipped out of most readers’ minds – after all, there’s no lack of classic fiction with an entirely male cast. By calling everyone “she” and “her”, on the other hand, the author draws attention to the unusual role of gender in her worldbuilding, in a way that only the most absent-minded reader could unsee.

Breq, even in universe, is communicating in a language that’s not her native one, and the book is dotted with hints to what is lost and gained in translation: gendered terms and expressions are the most obvious case, but other references are equally important to the worldbuilding, as well as to exemplify how language both shapes and is shaped by our cultural assumptions: for instance, in Radchaai the same word is used to mean both “citizen” and “civilised”, preemptively erasing the very concept of any valuable culture developed outside of the Imperial boundaries – and while the author doesn’t necessary dips into full linguistic relativity, one can’t help but wonder how much all this implies for the Radchaai’s perception of self and others.

While language and its subtleties play a significant role in Leckie’s worldbuilding, her writing style doesn’t come across as overly complex or obscure – quite the opposite, its thoughtful simplicity is what allows us to navigate with little guidance the fairly alien world we’re thrown into. Leckie doesn’t over-explain her setting, instead she gives us just enough information to get our bearings, allowing us to discover her world smoothly and organically; she only sparsely indulges in descriptions, but when she does so, she focuses on details that are essential to quickly establish both rules and ambience of her universe.

Plot Structure – On a surface level, one could describe Ancillary Justice as a quest for revenge: and indeed, when we first meet her, Breq is on her way to acquire a powerful alien weapon that she plans to use to murder the Lord of the Radch. For a revenge plot, however, it’s a surprisingly slow-paced one: except for a few action scenes, our main character is mostly seen spending her time musing over a number of existential questions, engaging in profound conversations with other characters, or recalling the most fateful moments of her past.

The way the story zigzags between present and past only enhances the impression of a diluted time progression, of a narration less invested in moving the plot forward than in fathoming all its depths. Nevertheless, in the end one can’t help but care about what happens to Breq and her companions; its deft exploration of characters and themes is what makes Ancillary Justice an engaging read, and what made me feel invested in the story as a result.

Setting – Ancillary Justice is set in a distant future in which humanity has entirely lost track of its terrestrial roots, and has expanded all over the galaxy; the most prominent political force is the aforementioned Radch, an interplanetary Empire ruled over by its undisputed leader, Lord Anaander Mianaai. The Radch is infamous for the disciplined loyalty of its subjects, as well as for its superior military technology, which notably includes the use of Ancillaries, that is to say reanimated soldiers who share a unified consciousness with the ship they serve.

Throughout most of its history, the Radch has been expanding its influence, conquering and annexing more and more inhabited planed; at the time of our main story, however, both the expansion and the creation of new Ancillaries have been halted by a series of reforms, and a treaty brokered with the powerful alien Presger serves as an additional reminder that the Lord of the Radch is not limitless in her power.

Now, if military assets and political influences are essential to explain the state of the universe, they are not the only defining trait of the Radch: its intricate system of hierarchies, patronage, favours, etiquette, and official religion, are portrayed perhaps not exhaustively, but with enough detail to suggest a much deeper complexity; as a result, the Empire comes across as a believable society with its own lived-in customs and traditions.

Since Breq spends most of her time on peripheral worlds, we also get to see what happen when a still vital local culture is overcome by the Radchaai influence. A significant plot arc is set on the recently conquered planet Shis’urna, and more specifically in the city of Ors: by all accounts, a small, apparently negligible corner of the universe, and yet its inner societal dynamics are thoroughly explored, and end up playing a key role in the outcome of the annexation.

It’s also worth addressing the existence of non-human societies – such as the feared Presger, as well as the briefly mentioned Rrrrrrs. While their influence has, in different ways, shaped the course of recent history, however, neither plays a major role in Ancillary Justice, except as an external menace and source of paranoia.

Characters – Breq Ghaiad of the Gerentate – this the self-assigned name of the former Ancillary One Esk Nineteen, segment of the ship Justice of Toren – is the main character as well as the narrating voice of the novel. As a former Ancillary, Breq struggles with the current limits of her human form, and has good reasons to ponder over the nature of identity, free will, and personhood – all things that should have been denied to her due to her status as an Ancillary, but that nevertheless she fully experiences. Despite her stoic demeanour, she’s greatly capable of care and affection, and her story is defined by her relations with Lieutenant Awn – a wise and compassionate officer from a humble background, who became a target of Anaander Mianaai’s wrath – and Seivarden – an uptight aristocrat who survived about 1.000 years in suspended animation, and is now struggling to come to terms with a unrecognisable world. Breq is apparently restrained in her emotional displays, but through her choices and actions we see how deeply she’s motivated by them, in a process that mirrors her development as an individual.

Breq’s nemesis is no less than Anaander Mianaai, the Lord of the Radch. Not unlike Ancillaries, the leader of the Empire split her consciousness into countless bodies that serve as her eyes and her hears, and that represent her rule all across the Empire. Her main motivation, even more than a hunger for power, is paranoia: indeed, the Empire comes from nothing else but her continuous strive to build a buffer space around her territory, repeated over and again through the centuries. Nowadays, however,

Themes – Due to its very premise, Ancillary Justice constantly deals with questions about what it means to be an individual. The main character used to be a hive mind, composed of a sentient ship and of its many Ancillaries; while her experience is way departed from our concept of individuality, Breq still refers to her past self as “I”, perceiving Justice of Toren and all its segment as a cohesive entity. Even before her separation, however, the protagonist had experienced some inkling of individuality: even before the destruction of Justice of Toren, the segment known as One Esk had started developing its own personality – a process certainly hastened by Anaander Mianaai’s intervention, but already visible in her interest in collecting songs, as well as in her special attachment to Lieutenant Awn. A similar but more dramatic fragmentation is experienced by the Lord of the Radch,

But, we may wonder, are other people really that different? Indeed, many characters through the story find themselves dealing with some form of dissociation or internal conflict, harbouring within themselves conflicting motives, as well as different codes of behaviour. Far from being just a bizarre plot device, the concept of a fragmented hive mind doubles as a reflection on the real meaning of identity, shedding an unusual light on how, behind our concept of individual consistency, we’re still very capable of contradicting ourselves, being different people under different circumstances, and even at times become our worst enemies.

Strictly tied to the theme of identity and interior conflicts is that of morality, justice, and free will. Throughout the novel, characters struggle with hard decisions, where their sense of justice is at odds with their role in the strict social hierarchy to which they belong; and while Ancillaries are supposed to be perfectly obedient, it turns out it may not always be the case. Breq often wonders to what extent her actions are her own, and in what measure they’re a result of her programming -but are the loyal subjects of the Radch really much more free, when the slightest insubordination may lead either to their death, or to a very thorough “rieducation”?

And of course, the Radch is a perfect allegory for power: a power born out of fear, but inherently driven to perpetual expansion; capable of conflicting means and goals, but ultimately sworn to its own self-perpetuation. Power dynamics are also shown in action at different levels: the Radch is, of course, the paradigmatic example of a colonialist force, but disparities are rampant even within its ranks; even though people are assigned their career paths through a supposedly impartial testing process, this is actually tailored to bring out the desired results, fuelling the illusion that those born among privilege are actually the most suited to hold all positions of power – with exceptions that are just meant to reinforce the rule.

Now, Leckie’s depiction of power is of course inspired by very real phenomena; at the same time, however, she challenges some of our assumptions by entirely removing gender roles, and by suggesting that in the Radch a darker skin is perceived as fashionable and even posh; on the one hand, this is a way to counteract some more or less unconscious bias, as well as forcing us to picture a world where the power (im)balances might be slightly different; on the other hand, it’s an implicit rebuke of the idea that all forms of oppression stem from patriarchy, and that once we removed Male Dominance TM the world would be equitable and at peace.

Overall Thoughts – I’ve probably lost count of how many times I’ve been coming back to this book, and every time I find a new way to appreciate it even more. It’s not an easy read, and if you think that ‘space opera’ equates to ‘action-packed planet-hopping adventures’, you may be taken aback. It is, on the other hand, a very insightful and layered book, rich with symbolism and food for thought, packaged in a fascinating setting and delivered through meaningful linguistic choices.

Leave a Reply